Most traditional Eastern martial arts have kata, hyeong, or training forms, that are practiced to develop technique, or to simply pass on a tradition. When certain people practice them, they look sharp and have a certain presence; when other people do them, they look like some kind of silly aerobic exercise. This article will help you understand the difference and apply it to your kata practice. Kata practice is, however, more than simply performing the steps well, though that is important. Another aspect of kata practice is the analysis of the movements in the kata to determine the more advanced techniques which are encoded there.

Get into the mindset.

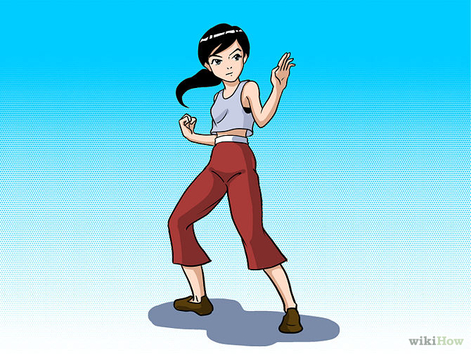

Perform your first step (or group of steps) against an imaginary opponent of exactly your size.

Relax between steps.

Some styles have kamae (combat postures) in the middle of the kata.

Understand that usually the last technique of the kata is the most dangerous or sophisticated.

In karate, the most important thing is kata.

Into the kata of Karate are woven every manner of attack and defense technique. Therefore, kata must be practiced properly, with a good understanding of their bunkai meaning.

There may be those who neglect the practice of kata, thinking that it is sufficient to just practice [pre-arranged] kumite that has been created based on their understanding of the kata, but that will never lead to true advancement. The reason why is that the ways of thrusting and blocking – that is to say, the techniques of attack and defense – have innumerable variations. To create kumite containing all of the techniques in each and every one of their variations is impossible.

If one sufficiently and regularly practices kata correctly, it will serve as a foundation for performing – when a crucial time comes – any of the innumerable variations.

However, even if you practice the kata of karate – if that is all that you do – and if your [other] training is lacking, then you will not develop sufficient ability. If you do not [also] utilize various training methods to strengthen and quicken the functioning of your hands and feet, as well as to sufficiently study things like body-shifting and engagement distancing, you will be inadequately prepared when the need arises to call on your skills.

If practiced properly, two or three kata will suffice as “your” kata; all of the others can just be studied as sources of additional knowledge.

Breadth, no matter how great, means little without depth.

In other words, no matter how many kata you know, they will be useless to you if you don’t practice them enough.

If you sufficiently study two or three kata as your own and strive to perform them correctly, when the need arises, that training will spontaneously take over and will be shown to be surprisingly effective. If your kata training is incorrect, you will develop bad habits which, no matter how much kumite and makiwara practice you do, will lead to unexpected failure when the time comes to utilize your skills.

You should be heedful of this point.

Correctly practicing kata – having sufficiently comprehended their meaning – is the most important thing for a karate trainee.

However, the karate-ka must by no means neglect kumite and makiwara practice, either. Accordingly, if one seriously trains – and studies – with the intent of approximately fifty percent kata and fifty percent other things, one will get satisfactory results.